Chapters

What is linear algebra?

Linear algebra is a branch of mathematics that deals with vector spaces and linear mappings between these spaces. It encompasses the study of vectors, matrices, systems of linear equations, and their properties and relationships. It is a fundamental part of modern mathematics and has many applications in computer science, physics, engineering, and other fields. In this chapter, we will introduce the basic concepts of linear algebra and discuss some of its applications.

Linear map is a function between two vector spaces that preserves the operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication. In other words, a linear map is a function that takes two vectors and returns a new vector that is a linear combination of the input vectors. Linear maps are fundamental to the study of linear algebra and have many applications in various fields.

Linear map f: (vector) -> (vector) is a function that satisfies the following properties:- Linearity: f(u + v) = f(u) + f(v) and f(αu) = αf(u) for all vectors u, v and all scalars α.

- Preservation of the zero vector: f(0) = 0, where 0 is the zero vector in the vector space. \( f = \begin{pmatrix} . & . & . \\ . & . & . \\ . & . & . \end{pmatrix} \)

\( v = \begin{pmatrix} . \\ . \\ . \end{pmatrix} \)

\( f(v) = \begin{pmatrix} . & . & . \\ . & . & . \\ . & . & . \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} . \\ . \\ . \end{pmatrix} \) Matrix Operation

In the expression \( f(x) = x^2 + 2x + 1 \), \( x^2 + 2x + 1 \) represents the function itself, and \( x \) is the variable.

Similarly, in the case of matrices, \( f(v) \) represents the function, where \( f \) is a linear transformation represented by a matrix, and \( v \) is the variable (vector) that the function acts upon.

So, just as \( x^2 + 2x + 1 \) is a function of the variable \( x \), \( f(v) \) is a function of the variable \( v \), where \( v \) is a vector.

Vector Spaces

A vector space is a set of vectors that is closed under addition and scalar multiplication. In other words, if you take any two vectors from the set and add them together, the result is also in the set. Similarly, if you take any vector from the set and multiply it by a scalar, the result is also in the set.

We will consider vector in Hilbert spaces. Hilber space:a set of vectors with complex coefficients

| Euclidean Space | Hilbert Space | |

|---|---|---|

| Ket vectors | |ψ〉= α|0〉+β|1〉α,β∈C | \( \vec{A} = a\hat{x} + b\hat{y} \) |

| Basis vectors | |0〉, |1〉, ... | \( a\hat{x} , b\hat{y}, .... \) |

| bra vectors | 〈ψ| | \( \vec{A} \) |

| Inner product | 〈ψ|φ〉 | \( \vec{A}. \vec{B} \) |

Complex Conjugates

In the context of complex numbers, the complex conjugate of a complex number z, denoted as z* or √z, is formed by changing the sign of the imaginary part of z.

If z = a + bi where a and b are real numbers and i is the imaginary unit, then the complex conjugate z* is given by:

$$ z^* = a - bi $$

In other words, the complex conjugate of a complex number simply reflects the point representing that number across the real axis on the complex plane. Geometrically, if you have a point representing a complex number in the complex plane, its complex conjugate is the reflection of that point across the real axis.

The complex conjugate is particularly useful when dealing with operations involving complex numbers, such as multiplication, division, and taking the modulus. For example, when multiplying a complex number by its conjugate, the imaginary parts cancel out, resulting in a real number:

$$ z \cdot z^* = (a + bi)(a - bi) = a^2 + b^2 $$

$$ z = x + iy, \quad z^* = x - iy, \quad (z^*)^* = z $$

This property is often used in various mathematical and physical contexts, including quantum mechanics, where complex numbers and their conjugates play a crucial role in describing the behavior of quantum systems.

Basis vectors

In linear algebra, a basis is a set of linearly independent vectors that span a vector space. In other words, a basis is a set of vectors that can be used to represent any vector in the vector space through linear combinations. The number of vectors in a basis is called the dimension of the vector space.

For example, in a two-dimensional vector space, the standard basis consists of the vectors (1, 0) and (0, 1), which span the entire space. Any vector in the space can be represented as a linear combination of these basis vectors.

Similarly, in a three-dimensional vector space, the standard basis consists of the vectors (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), and (0, 0, 1), which span the entire space. Any vector in the space can be represented as a linear combination of these basis vectors.

Example of linear combination \( \vec{v} = a\hat{x} + b\hat{y} \) \( \vec{v} = a\hat{x} + b\hat{y} + c\hat{z} \) where \( a, b, c \) are the scalar and \( \hat{x}, \hat{y}, \hat{z} \) are the basis vector

In quantum mechanics, the basis vectors are often denoted as \( |0〉= \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \) and \( |1〉= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \), which represent the possible states of a quantum system. These basis vectors are used to represent the state of a quantum system and to perform calculations involving quantum states and operations.

bra vectors

In quantum mechanics, the bra vector \( \langle \psi | \) is the complex conjugate transpose of the ket vector \( | \psi \rangle \). In other words, the bra vector is obtained by taking the complex conjugate of the ket vector and then transposing it.

If \( | \psi \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \end{pmatrix} \), then \( \langle \psi | = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha^* & \beta^* \end{pmatrix} \).

The bra vector is used to represent the dual space of the ket vector, and it is used to perform calculations involving quantum states and operations. The bra vector is often used in conjunction with the ket vector to represent the inner product of two quantum states, which is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics.

Orthogonal

In linear algebra, two vectors are said to be orthogonal if their inner product is zero. In other words, two vectors are orthogonal if they are perpendicular to each other. For example, in a two-dimensional vector space, the vectors \( \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \) and \( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \) are orthogonal because their inner product is zero. Similarly, in a three-dimensional vector space, the vectors \( \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \), \( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \), and \( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \) are orthogonal because their inner products are zero.

Orthonormal basis

In linear algebra, an orthonormal basis is a basis of a vector space in which the basis vectors are orthogonal to each other and have unit length. In other words, an orthonormal basis is a set of vectors that are mutually perpendicular and have a magnitude of 1.

For example, in a two-dimensional vector space, the standard basis \( \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \) and \( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \) is an orthonormal basis because the vectors are orthogonal to each other and have a magnitude of 1.

Similarly, in a three-dimensional vector space, the standard basis \( \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \), \( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \), and \( \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \) is an orthonormal basis because the vectors are orthogonal to each other and have a magnitude of 1.

In quantum mechanics, an orthonormal basis is often used to represent the possible states of a quantum system, and it is used to perform calculations involving quantum states and operations. An orthonormal basis is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics and is used to describe the state of a quantum system and to perform calculations involving quantum states and operations.

Delta Function

In mathematics, the Dirac delta function, or simply the delta function, is a generalized function that is used to represent a point mass or impulse. It is defined as a function that is zero everywhere except at a single point, where it is infinite, and the area under the curve is equal to 1. The delta function is often used in physics and engineering to represent a point mass or impulse in a system, and it has many applications in various fields.

In quantum mechanics, the delta function is used to represent the position of a particle in a quantum system. It is used to describe the probability of finding a particle at a particular position, and it is used to perform calculations involving quantum states and operations. The delta function is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics and is used to describe the behavior of quantum systems.

Inner product

In quantum mechanics, the inner product of two quantum states \( | \psi \rangle \) and \( | \phi \rangle \) is denoted as \( \langle \psi | \phi \rangle \) and is defined as the complex conjugate of the transpose of the ket vector \( | \psi \rangle \) multiplied by the ket vector \( | \phi \rangle \).

If \( | \psi \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \end{pmatrix} \) and \( | \phi \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \gamma \\ \delta \end{pmatrix} \), then \( \langle \psi | \phi \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha^* & \beta^* \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \gamma \\ \delta \end{pmatrix} = \alpha^* \gamma + \beta^* \delta \).

The inner product of two quantum states is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics and is used to calculate the probability of measuring a quantum state in a particular state. The inner product is also used to perform calculations involving quantum states and operations, and it plays a crucial role in the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics.

\( \langle \psi | \phi \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha^* & \beta^*

\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \gamma \\ \delta \end{pmatrix} = \alpha^* \gamma + \beta^* \delta \)

\( \langle \psi | \psi \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \alpha^* & \beta^*

\end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \end{pmatrix} = \alpha^* \alpha + \beta^* \beta = |\alpha|^2 +

|\beta|^2 \)

norm of a vector \( | \psi \rangle \) is given by \( \sqrt{\langle \psi | \psi \rangle} \)

1. \( |0〉= \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \) and \( |1〉= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \) basis

vector

2. \( \langle 0 | 1 \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} = 0 \)

basis vector

3. \( \langle 0 | 0 \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} = 1 \)

basis vector

4. \( \langle 1 | 1 \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} = 1 \)

basis vector

5. \( \langle 1 | 0 \rangle = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} = 0 \)

basis vector

Why linear algebra?

You just need to have an understanding of below list, what they are and what they mean

- derivatives

- integrals

- taylor series

- Vectors

- Dot Product

- Linear Combination

- Linear Transformation/ Matrices

- Inverse Transformation

- Basis

- Eigenvectors/Eigenvalues

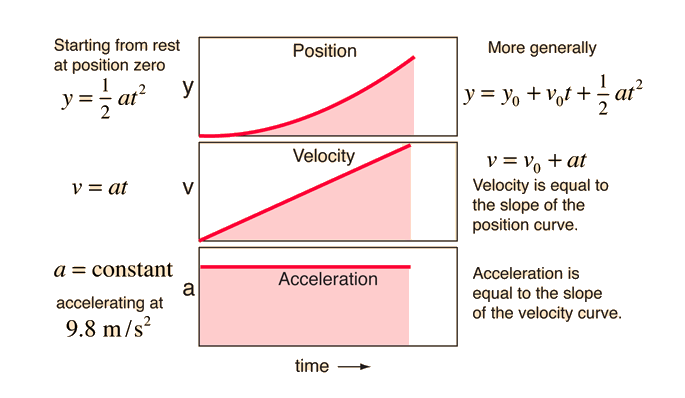

Figure 01: Rolling Ball

In classical physics, we use math to understand how objects move. Think of a boy rolling a ball on a table in (Figure 01). The ball travels smoothly through all the points you can imagine, never jumping from one place to another. It's like a continuous journey. At any point along its path, the ball has a single velocity, energy, and momentum. As it moves and interacts with its surroundings, these properties change gradually over time. We can't have the ball suddenly appearing in two places or having two different speeds. This consistent behavior is what we observe in nature, and it's described well by Newton's laws of motion. To explain this, we use functions that give us a smooth, single value for each property at any given moment. This approach helps us understand how things change over time without any sudden shifts or surprises.

Figure 02: Rutherfords Model

In classical physics, we use continuous functions to represent physical quantities. It's pretty straightforward, right? But sometimes, this classical way of thinking doesn't quite match up with what happens in the real world, especially when we dive into the tiny realm of atoms. Let's look at a hydrogen atom, which consists of an electron whizzing around a proton (Figure 02). According to classical physics, as the electron zooms around and gets closer to the proton, it should give off light energy. This is something we know from studying electricity and magnetism. We can measure this energy by checking the light emitted. By doing this, we can keep track of how much energy the electron has as it moves along its path. Now, in classical physics, we'd expect this energy measurement to be smooth and continuous. But here's the kicker: it's not. Even back when Rutherford proposed his model of the atom, he realized that something was off with this classical idea.

Figure 03: Bohr Model

Now, let's dive into the quantum world and see what really happens with a hydrogen atom and a detector. In the classical world, we'd expect to see a smooth, continuous pattern of energy readings like 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, and so on. But in reality, that's not what we find. Instead, our detector only picks up a few distinct energy values (Figure 03), like 10.02, 12.05, 13.01, and 13.56. No matter how many times we check, we always get the same set of values. Here's what we've learned from these experiments: First, it turns out that physical quantities in the quantum world can be discrete. This means they only have certain specific values, with nothing in between. This goes against the idea that everything must be continuous. Second, when we measure these quantities, we find that the specific value we get is random. But there's a twist some values are more likely to show up than others. So, before we measure anything, we can't predict exactly what value we'll get, but we can talk about the chances of getting different values. So, unlike in the classical world, where everything is smooth and predictable, the quantum world operates differently. We can't use continuous functions to model it we need something else.

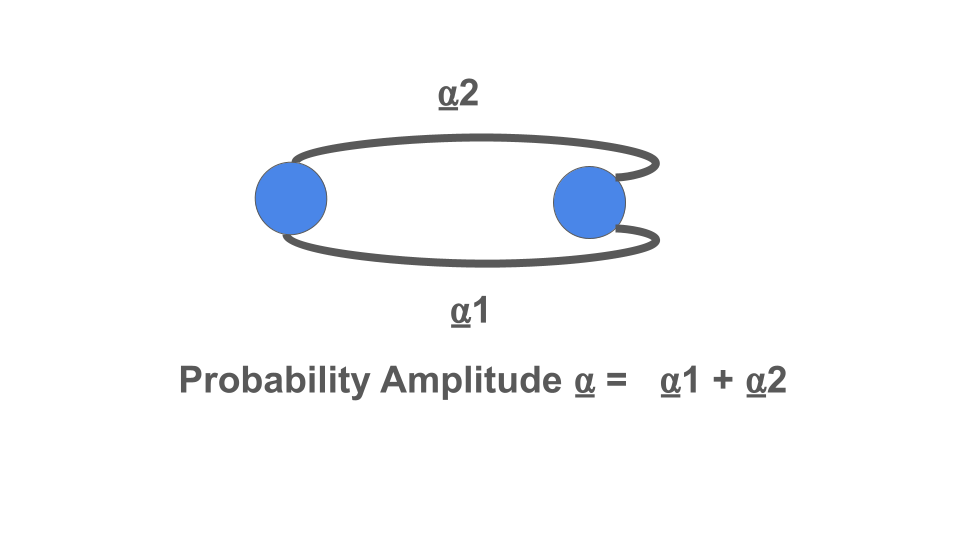

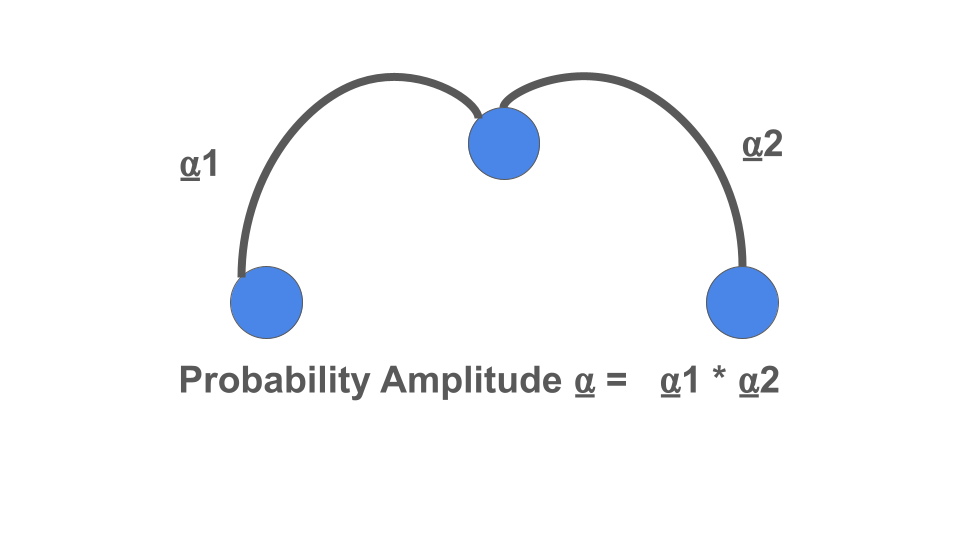

First, let's address the challenge of mathematically modeling randomness. Before measurements, particles seem to hold information about all possible energy states. How do we represent this? Well, let's say we have mathematical objects \( M_A , M_B , M_C and M_D\) for each energy state. Then, we combine them using an unknown "dot" operation, forming a collective representation of all energy states.

\( M_A . M_B . M_C . M_D\)

This dot operation could be addition, it could be multiplication, it could be something even more exotic. It's just some unknown way for us to combine our mathematical objects into one aggregate object that describes our particle before the measurement.Next, we also need to somehow codify the idea that some outcomes are more likely than others. So each mathematical object also needs to carry with it the probability of getting that particular outcome. Well the simplest way to do this is just to add a number in front of each mathematical object, a number that somehow encodes how likely each possibility is to occur.

\( a_A M_A . a_B M_B . a_C M_C . a_D M_D\)

Now, lets take a step back and look at what we have. Having studied a number of mathematical structures in your past, hopefully you begin to see that this looks suspiciously like a linear combination of some sort. You see that, right? This is our only lead, so let's go ahead and run with it: our particle is some sort of linear combination of all outcome-possibilities, which we'll assume are represented by some sort of vector. This may seem like a big leap, but hopefully you see how we came to these conclusions. Now let's move on to the discreteness problem. This is now a question about how we represent our physical quantities. We know that functions won't work; we need a mathematical object that allows us to sometimes extract discrete values. This is a little more difficult, but if we follow our lead on linear combinations, we may guess that maybe linear operators ,matrices, represent physical quantities. I mean, a matrix consists of a discrete set of numbers, so maybe we can somehow extract our physical quantities from that discrete set. So, putting it all together, we now have a really solid guess into how we want to model quantum mechanics! Particles are represented by a linear combination of vectors in some vector space, and physical quantities are represented by linear operators within that space. Now, if this seems somewhat contrived and unfamiliar, don't worry. We developed the framework of quantum mechanics in a handful of minutes, meanwhile it took the greatest physicists of the world years to arrive at these same conclusions. What matters is that you see why linear algebra is a good starting point for quantum mechanics.Expressing \( Y \) in the Form \( Y = UDU^\dagger \)

To express the matrix \( Y = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -i \\ -i & 0 \end{pmatrix} \) in the form \( Y = UDU^\dagger \), where \( U \) is a unitary matrix and \( D \) is a diagonal matrix, we first need to find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of \( Y \).

1. Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors:

The characteristic equation of \( Y \) is given by:

\[ \text{det}(Y - \lambda I) = 0 \]where \( I \) is the identity matrix and \( \lambda \) is the eigenvalue.

So, we have:

\[ \text{det}\left(\begin{pmatrix} 0-\lambda & -i \\ -i & 0-\lambda \end{pmatrix}\right) = 0 \] \[ \text{det}\left(\begin{pmatrix} -\lambda & -i \\ -i & -\lambda \end{pmatrix}\right) = 0 \] \[ \lambda^2 - (-i)(-i) = 0 \] \[ \lambda^2 - 1 = 0 \] \[ \lambda^2 = 1 \] \[ \lambda = \pm 1 \]So, the eigenvalues of \( Y \) are \( \lambda_1 = 1 \) and \( \lambda_2 = -1 \).

Now, let's find the eigenvectors:

For \( \lambda_1 = 1 \):

\[ Y - \lambda_1 I = \begin{pmatrix} 0-1 & -i \\ -i & 0-1 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & -i \\ -i & -1 \end{pmatrix} \]To find the eigenvector \( v_1 \), we solve \( (Y - \lambda_1 I) v_1 = 0 \):

\[ \begin{pmatrix} -1 & -i \\ -i & -1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \]This gives us the equations:

\[ -x - iy = 0 \] \[ -iy - y = 0 \]From the first equation, we get \( y = -ix \). Substituting this into the second equation, we get:

\[ -i(-ix) - x = 0 \] \[ x - x = 0 \] \[ x = 0 \]Thus, \( y = 0 \).

So, the eigenvector corresponding to \( \lambda_1 = 1 \) is \( v_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \).

For \( \lambda_2 = -1 \):

\[ Y - \lambda_2 I = \begin{pmatrix} 0-(-1) & -i \\ -i & 0-(-1) \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -i \\ -i & 1 \end{pmatrix} \]To find the eigenvector \( v_2 \), we solve \( (Y - \lambda_2 I) v_2 = 0 \):

\[ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -i \\ -i & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \]This gives us the equations:

\[ x - iy = 0 \] \[ -iy + y = 0 \]From the first equation, we get \( y = ix \). Substituting this into the second equation, we get:

\[ -i(ix) + x = 0 \] \[ -x + x = 0 \] \[ x = 0 \]Thus, \( y = 0 \).

So, the eigenvector corresponding to \( \lambda_2 = -1 \) is \( v_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \).

Now, for \( \lambda_1 = 1 \), we need to find another linearly independent eigenvector since the one we found is the zero vector.

From our equation \( -x - iy = 0 \), we can pick \( x = 1 \) and \( y = i \), which gives us another eigenvector \( v_1' = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ i \end{pmatrix} \).

Now, for \( \lambda_2 = -1 \), we'll use the same process to find another linearly independent eigenvector. From our equation \( x - iy = 0 \), we can pick \( x = 1 \) and \( y = i \), which gives us another eigenvector \( v_2' = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ i \end{pmatrix} \).

2. Constructing Matrices \( U \), \( D \), and \( U^\dagger \):

Now, we construct the matrix \( U \) using the eigenvectors:

\[ U = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ i & i \end{pmatrix} \]Now, let's construct the diagonal matrix \( D \) using the eigenvalues:

\[ D = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix} \]Now, let's find \( U^\dagger \), the conjugate transpose of \( U \):

U^\dagger = U^* = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & i \\ 1 & i \end{bmatrix}

3. Calculating UDU^\dagger:

Finally, we have:

UDU^\dagger = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ i & i \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & i \\ 1 & i \end{bmatrix}

= \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ i & i \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ -i & -i \end{bmatrix}

= \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 2 \\ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}

Thus, we've expressed \( Y \) in the desired form: \( Y = UDU^\dagger \).